- I’ve messed up my calendar and have to explain to my partner that, instead of going out with them this evening, I must work late

- I’ve messed up my roadmap and have to explain to my boss that, instead of being able to supply a vaccine just in time to save the world from a pandemic, we have to go back to the drawing board while our competitors make a fortune

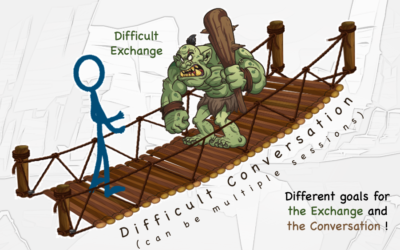

As for any Difficult Conversation, emotions will be involved and we have been representing them (see earlier articles) as a troll on a bridge [1]. In both the above cases, we can imagine emotions raging in both myself and in my partner/boss. We’ve got a big troll to tame!

So what do I say to my partner/boss in order to help them keep calm and, secondly, what do I say to myself in order to manage my own emotions?

Furthermore, should I actually talk about emotions and, if so, how?

We suggest that it’s imperative to communicate accurately and benevolently about emotions in these circumstances, both to others and to ourselves.

Feelings insist on being heard

If I ignore the hurt, the rage or the fear of the person I am talking to, then they will invariably keep signalling hurt or rage or fear until I acknowledge their feelings somehow. They may look more and more miserable, talk louder and louder or maybe just leave the room/cut the call.

The same goes for my internal self. Several psychological models use the idea of multiple voices within a person, our internal dialog being a conversation between these voices. If the voice that’s screaming “I hurt!”, “I’m mad” or “Get me out of here!” is ignored, then it will keep screaming. In fact, it will scream so loudly that I won’t be able to think.

The troll therefore represents two sets of emotional commotion: my own and that of the other party. To reconcile a Difficult Exchange, I have to calm the troll completely, so that he’ll let me past and a normal conversation may continue. This means not only choosing the right words to say out loud but also paying attention to my internal dialog.

My internal dialog strongly affects my feelings

As we’ve already discussed, any interpretations hidden in my observations may irritate the other party. At the same time, the story I tell myself determines my emotional state and the more accurately I tell this story, the calmer I will tend to be. Hence, when I pause to consider a situation, our guidelines concerning concealed judgements, rules and suppositions still apply.

For these guidelines to be effective, I must develop the habit of pausing. This has to become instinctive in order to have a chance of overcoming the instinctive nature of certain judgements, rules and suppositions.

For example, suppose I get copied on an email to my boss (N+1) from my team member (N-1). It contains a suggestion for something that is my direct responsibility. My immediate reactions are:

- What a lack of respect! (a judgement)

- A team member should never communicate with their N+2 on this topic without first contacting their team leader (a rule)

- They did this because they want to look good! (a projection and an assumption)

Pause. I know that I am getting upset and so I examine my internal dialog. What story am I telling myself?

The story is the one summarised by the three bullet points above. Simply realising this calms me a little and, though still annoyed, I decide to call my team member and find out why they sent the mail (intention to understand). “I just received a copy of your email to X. What was the reason for it?” (fact + invitation).

It turns out that they had met my boss by chance and had been asked to send this mail without delay. They had called me twice, got no reply, waited a bit and then sent it, with me on copy.

I still disagree with their decision to send the mail, but the story I am telling myself has been completely rewritten. I am now calm and engaged in a normal conversation with my team member.

Over the years, all sorts of judgements, rules and suppositions have become instincts – they kick in immediately something happens or is said. I conceal them in my speech because they have become invisible to me, and I do this both when I talk out loud and in my internal dialog.

We therefore see that making and transmitting observations and identifying, managing and expressing feelings are intricately connected topics. I observe and relate facts about a situation, this affects the feelings of others and of myself also. I observe these feelings and may comment on them and this, in turn, affects the general emotional situation.

To teach people to deal with this level of complexity, we have simplified our guidelines as far as we are able while, at the same time, maintaining the effectiveness of approaches such as NonViolent Communication (see Difficult Conversations, Bridges and Trolls and subsequent articles). As just mentioned, pausing to calm oneself and decide on intentions is a key first step. Then, we suggest that deciding what to actually say becomes simpler if I focus on accuracy of expression [2].

Focus on accuracy – it makes things simpler

It’s relatively easy to understand the importance of accuracy when describing the facts of a situation. However, “accuracy” is not a word that’s commonly associated with feeling (or needs, though this topic is for a future article).

Yet, to communicate facts and feelings well, we must follow the same path. In our last article, we looked at how to communicate our observations about a situation in the least provocative way possible, and we argued that hidden interpretations fuel conflict. One way to explain this is to examine the role of precision in communication.

For example, “It is important to release the software this week” conceals a judgment. The sentence is subjective but expressed as an absolute fact. It is therefore imprecise and likely to provoke a response of “Nonsense! It’s not nearly as important as XYZ…”.

Similarly, the inaccurate expression of feelings can inflame a difficult conversation. If I say, for example, “You made me sad,” the other party might, with some justification, respond, “Don’t dump the responsibility for your feelings on me! I simply told you the truth. It’s up to you to do what you want with it!”.

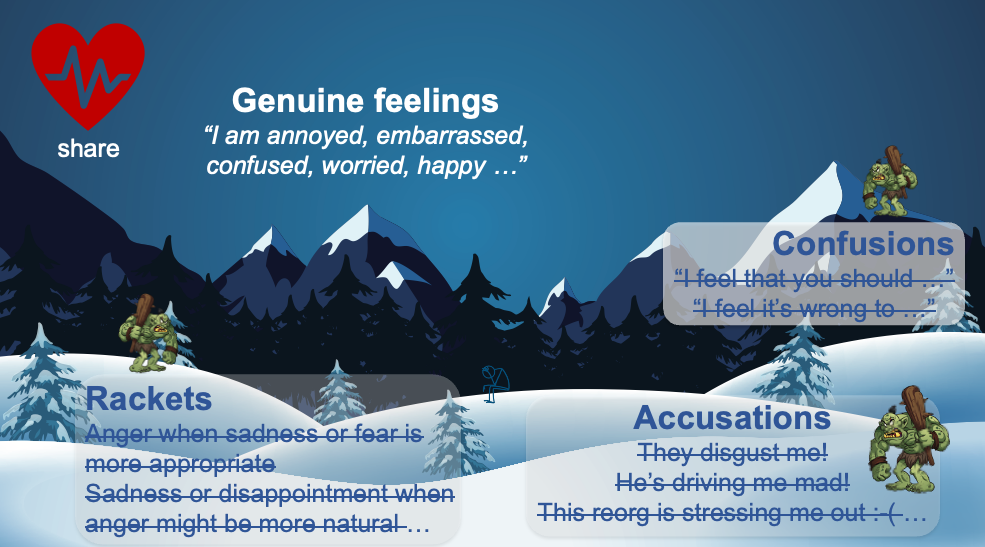

This brings us to three particular sources of inaccuracy to watch for when expressing emotions: accusations, confusions and rackets.

Accusations

For example, when someone says, “You made me sad”, they really mean, “Having thought about what you said, I am sad”. Note that the latter statement is undeniable. I am the only person with direct access to my thoughts and emotions and so when I use the first person singular, I, to say what’s going on inside me, others can’t reasonably argue.

On the other hand, “You made me sad”, is an accusation! Consider a few other accusations that we find in casual speech:

- It makes me furious!

- They disgust me!

- He’s driving me mad!

- This reorganisation is stressing me out!

- They scare me to death!

- You’re annoying me!

- It makes me depressed!

- This software drives me nuts!

The common factor in these examples is that the speaker is transferring responsibility for their feelings to someone or something else. They are saying that X caused a particular set of emotions within them though, as we have seen, the real cause is the story they told themselves about X. Hence, the above statements are inaccurate and may fuel an argument.

I will avoid this pitfall if I aim to describe my feelings accurately (even though complete accuracy is an elusive goal) and, in doing so, I am bound to use the first person singular. I will use “I”.

Confusions

When someone expresses, for example, an opinion as though it were a feeling, then they are talking inaccurately. When they say, “I feel that you’ve made a mistake”, for example, they could mean, “in my opinion, you’ve made a mistake”, or perhaps, “you idiot, look what you just did!”. Either way, someone else making a mistake is not a feeling!

Here are a few other familiar confusions:

- “I feel it’s your responsibility to <do X>…”(request?)

- “I feel they don’t like us…” (projection?)

- “I feel that’s expensive…” (opinion?)

- “I feel that <X> is important…” (value?)

- “I’m sorry you did that…” (accusation?)

- “I’m afraid you’ll have to…”(direction?)

- “I’m afraid I’ll have to…”(an excuse for what I’m about to do?)

- “I regret to tell you that…”(I’m telling you!)

All of the examples start with “feeling words”, but they are not expressing emotions – at least, not clearly and directly. For this reason, we consider the speech to be inaccurate, even if “I” is used throughout.

To understand why this can be problematic, we invite you to replace each phrase with something more accurate and hence less provocative. For example instead of, “I feel it’s your responsibility <do X>…”, perhaps we could use, “I believe you are responsible for Y, so please could you <do X>”?

Rackets

The person says they are feeling one thing, but deep down they are feeling another. For example, they say they are angry but, in fact, they are afraid.

When one feeling is expressed as being another, this is the sign of an old scar. Of programming early in life. For example, a lot of men will express fear as though it were anger and many women will express anger as sadness, because of their social programming. These are generalisations, of course, used to illustrate the point.

Given the deep seated nature of racket emotions, there is no quick fix. We don’t have a formula for dealing with them. In practice, some people become conscious of their racket emotions independently, then deliberately work to reduce their hold. Others get external help – a therapist, a coach or a friend, for example.

However, there is a short term benefit from being aware of racquet emotions: it can help us to better understand the emotions involved in a Difficult Exchange. The emotions we see, ours and the other party’s, are not always what they seem to be. When we see anger, the authentic emotion may be fear. When we see sadness, perhaps there’s something else going on?

We’ve represented this emotional cocktail as a troll and we now see that trolls, like people, are complicated 😉.

Beware of brutal honesty

We have asserted that aiming for accuracy can simplify decisions on what to say during Difficult Exchanges and , so far, we have deliberately avoided a discussion about honesty.

Someone who is honest strives to be accurate, but expressing oneself accurately is not sufficient to achieve honesty. I can inform a colleague that they have been put forward for a job – an accurate statement – without mentioning that someone else is certain to get the position. The colleague was put forward only to satisfy certain bureaucratic requirements. This is hardly honest – I am guilty of omission.

This example notwithstanding, everybody has to decide what is and isn’t honest for themselves and being honest is a personal choice. In our view, striving for accuracy takes us in the direction of honesty and being as honest as possible is a tremendous help in reconciling a Difficult Exchange. After all, how could anyone reasonably object to what I say if I’m honest?

But brutal honesty can be as bad as none at all.

As Levine et al explain [3], the harsh truth can be too much for some people sometimes and I therefore have to temper accuracy and honesty with benevolence. That is, I must pay careful attention to the other party, using intelligence and empathy in order to judge their ability to process my message.

This is particularly important when expressing feelings since doing so is likely to make the other party feel obliged to reciprocate. However, if they are uncomfortable doing so, I should notice this and take it into account, perhaps saying less than I planned.

‘Tis terribly tricky taming trolls

The examples that we opened with – admitting an error to a partner and to my boss – illustrate several of the fundamentals for dealing with Difficult Exchanges (taming the troll). We must focus initially on getting back to a normal conversation, free from heated emotions. Achieving this requires careful management of our external and internal communication, else our agitation will prevent clear thinking. This communication must be as accurate as possible, whether we are talking about facts or feelings. Anything else is likely to further provoke the troll!

In a previous article, we looked at how interpretations – judgements, rules and suppositions – can pollute factual observations, and we’ve seen how this is relevant to understanding and expressing feelings also. We have now added accusations, confusions and rackets to the checklist. In our next publication, we’ll see the key things to look out for when expressing needs.

Andrew Betts and colleagues

Last modified: 31 July 2022

[1] The number of possible emotions is relatively small – between 4 and 7, depending on interpretations. Joy, anger, fear and sadness are widely accepted. Surprise, disgust and guilt appear in some lists. Feelings are combinations of emotions and so they are many – in the range of 50 to 100. See https://www.cnvc.org/training/resource/feelings-inventory, for example.

[2] Accuracy of an expression is how close or far off it is from the true meaning, while the precision of an expression is a measure of its distinctiveness from another expression.

[3] Difficult Conversations: Navigating the Tension between Honesty and Benevolence; Emma E. Levine, Annabelle R. Roberts, & Taya R. Cohen

---

Other articles in this series

English articles : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , summary and notebook

Traductions en français : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , sommaire et cahier

Your feedback and suggestions

The Difficult Conversations eBook and articles are the result of many hours of collaborative work and they build upon a huge base of established wisdom.

I am grateful to everyone involved so far – trainees, fellow trainers and coaches, other authors … and I would also appreciate your comments and suggestions!

There is an online form or, if you prefer, an email to contact@icondasolutions.com would be fine.

As you may have noticed, ...

... the topics in this series on Difficult Conversations are organised hierarchically:

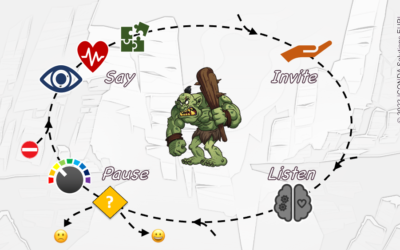

- Article 1: At the top level, a Difficult Conversation can be imagined as a bridge with a troll blocking the way, where the troll represents the Difficult Exchange which has to be sorted out before a normal conversation can resume. Our challenge is to tame the troll.

- Article 2: At the next level, we break our troll-taming method down into a four step loop: pause, say, invite and listen/decide. We go around this loop until we've Reconciled the Difficult Exchange and have returned to a normal conversation (dialog).

- Articles 3-7: Finally, each of the four steps has its own internal details and the refinement of these details takes us deeper still, as with any substantial subject.

We invite you to use the tools and models described in these articles to guide your practice and we hope that you find this hierarchical description helpful.

Comments, suggestions and enquires: contact@icondasolutions.com