A few weeks ago, in a parallel universe, a customer called and said, “Andy, we’ve been trying to use the software you sold us and have run into difficulties. In fact, we missed a critical delivery last week and management is telling me that failure this week is not an option. I’m very nervous, as well as frustrated and fed up. I need to feel secure in my job and confident of my own ability to manage this project. I also want to have real partnerships with our suppliers. However, working with your support guys last week didn’t work out well. Can you help?”

What could I say? I could see the pain that they were in, I didn’t feel attacked and I threw myself into finding a solution for them.

After things had been sorted out, I started wondering why I had felt so committed to helping this customer. They had not told me exactly what to do, but what had they said? And what had they not said?

Express needs that others can relate to

We believe that a crucial skill in difficult conversations, exemplified by the customer in the parallel universe, is expressing needs at a level other parties can relate to.

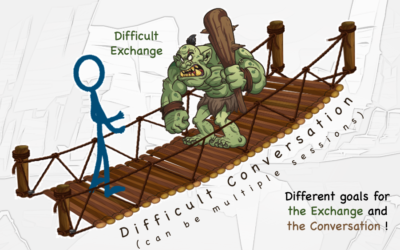

This article continues a series on Leading Difficult Conversations and a method developed for the critical part of such conversations, the Difficult Exchange. The idea is first to focus on this exchange, attempting to calm emotions and return to a normal conversation. Until this has been achieved, any goals one had for that conversation have to be put on hold. The highly charged emotional content of the exchange is represented as a troll on a bridge, the bridge itself being the conversation as a whole.

The parallel universe situation just described has all the necessary ingredients for a difficult conversation: the stakes are high and emotions could easily run high too. However, the customer was such a good troll tamer that the troll didn’t even wake up!

In the real universe, the customer called my boss and threatened to bring the sky down if we didn’t send an expert to sort out the problem immediately, on site somewhere or other. My boss then called me, I defended myself and my team and then, extremely annoyed, started working out how to appease the &%**#$ customer.

In the parallel universe, however, the customer started factually then expressed their feelings in a responsible way and did the same for their needs. I found these needs easy to relate to since I too need job security and when I have projects to manage, I also like to feel confident doing so. Since they expressed their needs at a level that I could relate to, I found myself more inclined to listen and to help.

Getting the level right

Needs can be imagined as being organized in layers with fundamental needs at the bottom – security, connection, rest, etc. – and progressively more complex and specific needs higher up – physiotherapy, internet access, cannabis, etc.

Everyone has the same fundamental needs to some degree, whereas some high level needs are shared by very few people – the need to lay on a bed of nails, for example. Hence, the better I am able to express my needs at a low level, the more likely it is that the other party will understand.

For example, if I say that I need job security, most people will be able to relate to that. If instead I say that I need my software problems sorted out by the end of next week, then the other person is left to guess that my fundamental is for job security. That’s asking a lot!

However, it’s not always necessary to descend to the level of fundamental needs in order to get understood. This depends on how much I have in common with the other party. If I say, “Boy, do I need a pizza” to a friend who understands that “pizza” means stopping work and having a relaxing beer, then I don’t need to spell out my fundamental need. They know full well that I am not threatened by starvation – this is not a physical security need!

Pizza talk aside, we tend to express needs at a level other people do not understand, obliging them to guess at what is motivating us. Since they react to what we say, rather than to the fundamental need behind what we said, there is a good chance of misunderstanding and that we won’t be satisfied by their response. For example:

- “I want to quit this job” may be the result of a more basic need, “I need a new challenge/more excitement”

- “I would like a salary increase” may be hiding, “I need to feel valued” or perhaps, “I need to feel secure”

- “I want to leave [the party] now” may be motivated by the need for calm and rest.

- “I want you to clear up your room” could have been preceded by , “I need to keep us all organised, clean and safe”

- “I quit!”

- “I deserve a raise!”

- “Let’s go!”

- “Clear up your room!”

We say these sorts of things out of habit and also because it’s quicker and easier than thinking about what we really need and expressing ourselves accurately, in a way that the other party can readily understand.

However, before I am express my needs at any level, let alone the right one, it is necessary to understand what they are. Given that lists of generic needs typically contain 60-90 items [1], this can be a rather formidable task. We’d therefore like to suggest a way to simplify it.

Consider the type of need

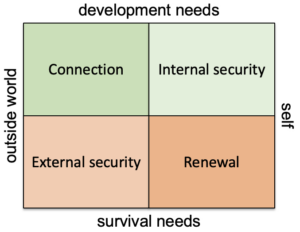

Our suggestion is to consider needs in four quadrants. In our diagram, the two quadrant to the right concern the self, while the two on the left relate to the outside world. The two lower quadrants concern survival, and the upper two development [2].

These concepts allow us to divide needs into four easily-remembered types:

- External security needs

- Protection I need from the outside world

- eg. sufficient food, physical protection, financial assurance

- Internal security needs

- Personal needs for psychological wellbeing

- eg. sense of meaning, centeredness, confidence

- Connection needs

- Needs in relation to society and other people

- eg. love, belonging, appreciation

- Renewal needs

- Restorative protection I must give myself

- eg. play, calm, rest

In a given situation, it is usually straightforward to assess which of these four types are concerned and, having done this, I consider the sub-types within them. By organising my thought in this way, I find that I can more quickly home in on a useful result.

To experiment with this, we’ve produced a simple practice tool. It consists of a list of 50 sub-types in a spreadsheet table. You are invited to explore the list, deciding which of the four types each sub-type belongs to. A reference set of choices is provided and the sheet automatically indicates if your choice agrees with the reference.

We hope that experimenting with this tool will help you bring your needs vocabulary more readily to the fore. Furthermore, when a need comes to mind, we invite you to consider the following question …

Is it is a real need?

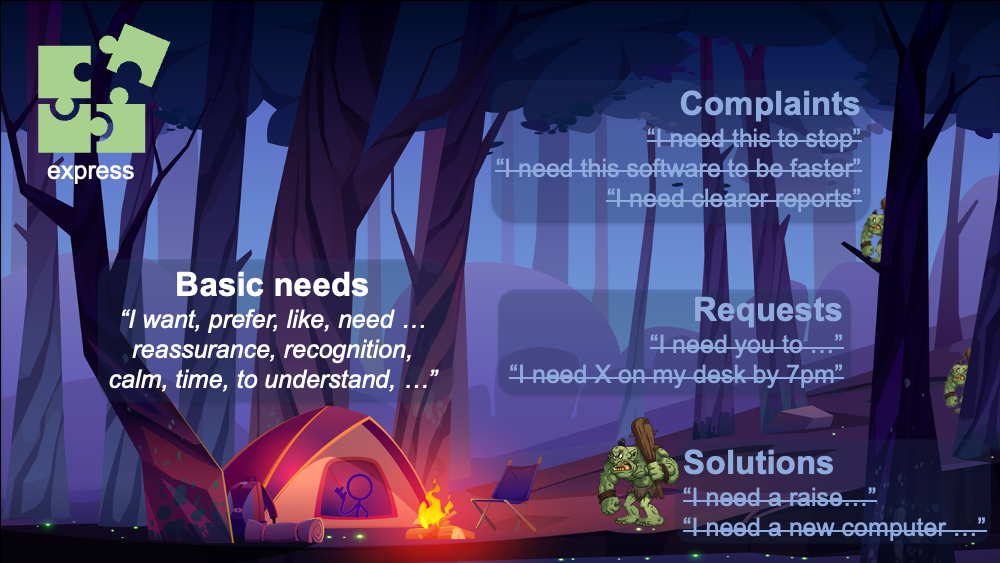

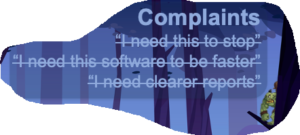

Perhaps because pinpointing my exact need is a demanding business, I slip easily into other forms of expression, even when I start a sentence explicitly with, “I need …”.

For example:

- “I need clearer reports” is a complaint

- “I need you to move to another room” is a request

- “I need a new computer” is a solution to a problem

We assert that these three types of expression are inaccurate. The verb does not match the object of the sentence. I might as well say, “I see an imagination” or “I hear a voyage” – putting these words together makes no sense!

As discussed in our articles on expressing observations and feelings, such inaccuracies fuel misunderstanding and argument. They provide an excuse for a defensive reaction. In a Difficult Exchange where such a reaction is easy to trigger, almost imperceptible errors of this kind can cause things to go off of the rails.

Complaints, requests and solutions are wolves in sheep’s clothing – the sheep is the real need, and it has strayed from the flock!

Complaints

In the best case, the other party is clairvoyant and guesses correctly that, when I say that I need clearer reports, what I really need is to better understand the subject in question (which will require much more than clearer reports, by the way).

Or they could be confused, and we could enter into a long, useless conversation about what constitutes a clearer reporter.

Or perhaps they are obliging, in which case they might waste hours polishing the document.

Of, as discussed, they could get defensive: “But my report is perfectly clear!!”. In this case, we have antagonised the troll and our Difficult Exchange has become even more difficult.

On the other hand, even though it might take a bit more thought and a few extra words, I could try something like: “I’m really having trouble understanding what you’re working on and when I read this report, it’s no clearer to me. To be able to manage the project properly, I need to get to grips with this subject. However, my schedule is crazy, and so I also need to be extremely efficient in doing so. Let’s discuss what can be done.”

Requests

For example, “I need you to move to another room” can be interpreted in several ways, and if the other party is in a bad mood, finds the room reservation system particularly irritating or simply doesn’t like me, this ill-expressed need can cause problems.

Do I mean that this room is critical to some important work and that if I don’t get it now, something bad will happen? Or is it that I have gone through the procedure for reserving the room and I consider that it’s my right to have it now? Or have the builders just arrived and the walls are about to be torn down?

Whatever the answer, we hope it’s clear that the construct, “I need <someone> to <do something>” should be banned from our list of stock phrases. The fix is simple: I must just say what I mean. “I want you to …” or “I would like you to …” are more straightforward and accurate, avoiding confusion both for me and the other party.

And, “I need <what I really need> and so I would like you to …” could be even better!

Solutions

For example, a new computer could be a solution for all sorts of problems and needs, and statements such as, “I can’t get on the web again; I need a new computer” are wide open to counter arguments. A cooperative person might respond by trying to understand the problem and needs in more detail before suggesting one or two solutions but, in the context of a difficult conversation, a retort such as this is more likely, “There you go again! If you would only learn to configure your network connection properly, you wouldn’t get these problems!”.

Why irritate the troll like this? Why not explain, “I can’t get on the web again and when I think about the number of times I get stuck like this, I get down. I don’t like technology and I haven’t the patience to learn how web connections work. I need a simple solution that lets me get my work done without having to bother other people.” Clearly, this type of response is less likely to result in irritation and resistance. Also, it opens up multiple solutions.

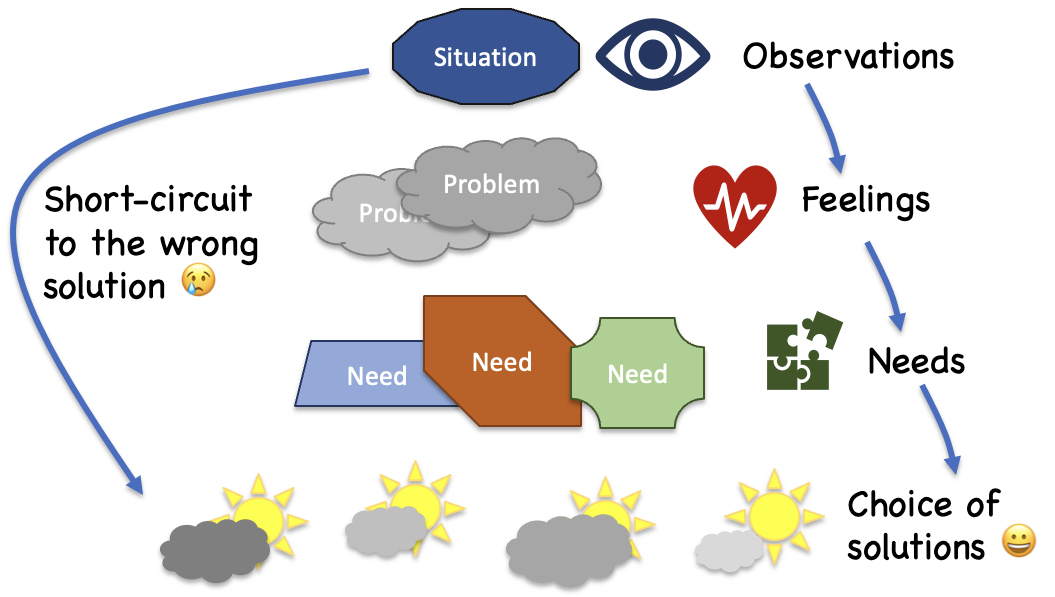

Needs open up multiple solutions

Let’s take a step back and look at why we’ve been recommending that, to develop skill at reconciling Difficult Exchanges, we should work on the expression of observations, feelings and needs. We’ve seeing that their accurate expression will tend to calm the emotional troll that we’re facing on the bridge of conversation. However, there’s even more to it than that.

Once emotions have settled down and the conversation is returning to normal, I must start looking for a solution with the other party. Something that we can agree on.

If we see the situation in the same way (since we have exchanged observations and made necessary adjustments), if we have both expressed our feelings and if we’ve explained to each other what we need in order to feel better, then all that’s left is a puzzle to be solved. Which solution best satisfies all these needs?

The alternative, much trodden path, is to start a conversation by rapidly summarising the situation and jumping to a solution … and this is often done through complaints, requests and solution statements, as described above. We call this approach a “short-circuit” and it’s main characteristic is that it takes us straight to one solution, ignoring all the other possibilities and preventing the other party from discussing them.

Hence, expressing needs accurately – talking about real needs, not making complaints, requests or pushing solutions – is key not only to reconciling the Difficult Exchange within the conversation, it is opens the way to finding a solution to the matter in hand. That is, to a successful outcome of the Difficult Conversation itself.

Andrew Betts and colleagues

Last modified: 31 July 2022

[1] Needs and types of needs have been enumerated by, for example, Maslow and the NonViolent Communication community. There are many lists of needs, too long to remember but interesting to consult and play with. For example: https://www.cnvc.org/training/resource/needs-inventory and https://communicationbienveillante.eu/cnvbesoin/

[2] Survival and development needs are reminiscent of the lower two and the upper three levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs respectively.

---

Other articles in this series

English articles : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , summary and notebook

Traductions en français : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , sommaire et cahier

Your feedback and suggestions

The Difficult Conversations eBook and articles are the result of many hours of collaborative work and they build upon a huge base of established wisdom.

I am grateful to everyone involved so far – trainees, fellow trainers and coaches, other authors … and I would also appreciate your comments and suggestions!

There is an online form or, if you prefer, an email to contact@icondasolutions.com would be fine.

As you may have noticed, ...

... the topics in this series on Difficult Conversations are organised hierarchically:

- Article 1: At the top level, a Difficult Conversation can be imagined as a bridge with a troll blocking the way, where the troll represents the Difficult Exchange which has to be sorted out before a normal conversation can resume. Our challenge is to tame the troll.

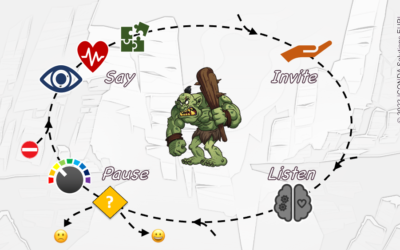

- Article 2: At the next level, we break our troll-taming method down into a four step loop: pause, say, invite and listen/decide. We go around this loop until we've Reconciled the Difficult Exchange and have returned to a normal conversation (dialog).

- Articles 3-7: Finally, each of the four steps has its own internal details and the refinement of these details takes us deeper still, as with any substantial subject.

We invite you to use the tools and models described in these articles to guide your practice and we hope that you find this hierarchical description helpful.

Comments, suggestions and enquires: contact@icondasolutions.com