If you’re hurtling downhill, over rocks and tree roots, on a cross-country bike, what do you concentrate on?

If you’re driving on a crowded motorway, with cars criss-crossing in front of you, what do you concentrate on?

If you’re in a meeting, with clever arguments coming at you from left and right, what do you concentrate on?

Now, spot the wrong answer:

- The rocks and the roots

- The other cars

- What I’m going to say next

Of course, I should be listening, not composing my next contribution. What I end up saying may be important too and I must be prepared, of course, to say the right thing once I’ve listened and understood those around me. But I can’t know (and certainly mustn’t rehearse) what I’ll say before then.

Listening, like dodging rocks, roots and cars, is the secret to survival.

However, in order for me to be able to listen, the other party must be allowed to say something. Perhaps it will even be necessary to invite them to do so …

Invite

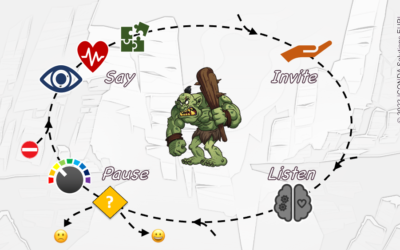

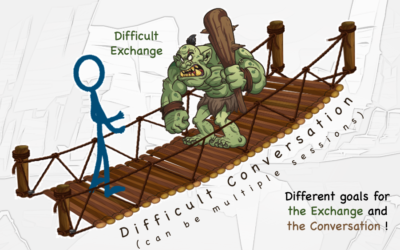

In preceding articles, we looked at how factual observations, feelings and needs might be expressed during a Difficult Exchange, likening such an exchange to meeting a troll on a bridge. The bridge represents the conversation while the troll is the turmoil of emotions that have to be sorted out before a normal, professional conversation can resume. The troll can be tamed using a looping flow. Now that the main elements of this flow have been presented, we come to the question of how to close the loop.

We’ve seen that, if I do a good job of expressing my observations, feelings and needs, then the other party will probably respond in kind, stating their view of the situation and how it affects them. Indeed, we drew attention to the danger that the other person might feel obliged to respond in kind, and this could take them dangerously outside their comfort zone. We therefore reiterate the need to combine honesty with benevolence during a Difficult Exchange.

Assuming that this danger has been avoided, it’s often unnecessary to explicitly invite the other party to talk, since they may spontaneously respond in kind. If an invitation seems necessary however, then I keep it as simple and clear as possible, accepting the possibility that the other person may decline to respond. Simple sentences are in order such as, “What do you think?”, “How do you see this?” or, “Could you tell me what you’ve understood from what I just said?”.

When doing so, I’m careful not to substitute a request for an invitation. I can easily fall into this trap though my impatience to reach goals which, as discussed, should be put on hold until the Difficult Exchange has been dealt with.

For example, if my team member is still fuming, unable to accept my constructive feedback, then I must not say something like, “Of course, I am interested to know what you think, so please can you complete the review form and send it back to me by tomorrow lunchtime”. It would be far better if the request, “please can you complete the review form…” were delayed until the troll had been tamed – i.e. emotions were no longer dominating the conversation[1].

One of the most effective ways to tame a troll is to …

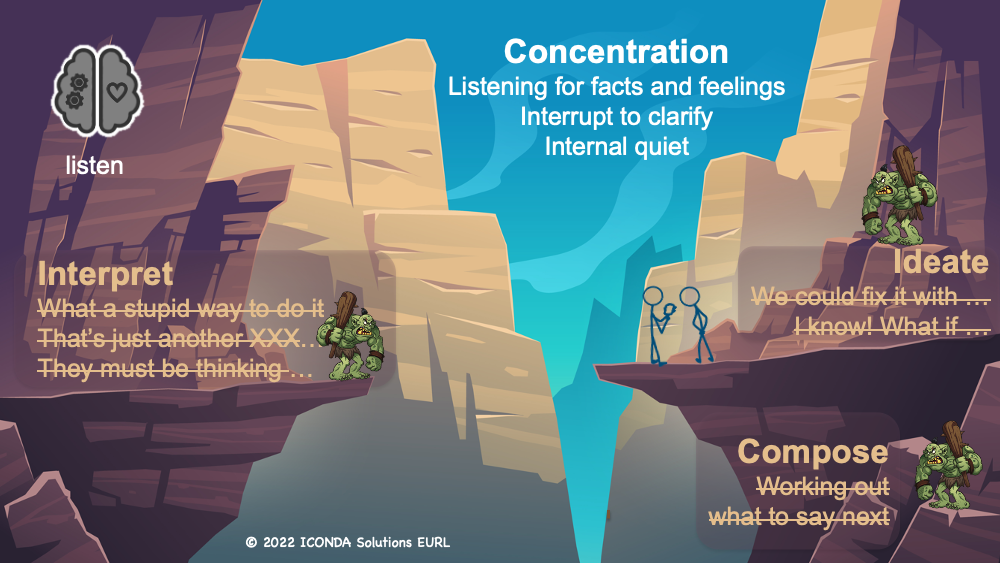

Listen

Listening is paying attention. Concentrating on what others are saying, on how they are saying it, on their reactions to what is being said and on my reactions too.

Listening is an internal quietness, but it is not being quiet.

It is Ok and necessary to interrupt if I am unable listen any more and need a moment to absorb what has been said, for example. Or to ask for clarification of a certain point[2].

It’s not Ok to interrupt in order to “make it about me” – to show how clever I am or to recount an anecdote that has just come to mind. Someone striving to communicate their problems and needs doesn’t want to hear my war stories!

Quality listening is close to meditation. Indeed, meditation is a form of listening, letting go of interfering thoughts in order to hear what’s going on inside, and it’s a good way to practise more general listening skills.

These skills allow me to harvest and understand two types of information: facts and feelings. The harvesting is done through listening while understanding requires analysis and empathy, for facts and feelings respectively:

- To harvest data, listen

- To understand the factual aspect, analyse

- To understand the emotional content (feelings[3]), empathise

Strictly speaking, understanding is a matter for the Pause step (see the Troll-Taming Loop). Furthermore, the need for analysis and empathy brings us back to guidelines given on expressing observations and feelings, since expression and understanding are two sides of the same coin. Just as it helps to follow a certain discipline when explaining facts and feelings to others, it is equally helpful to avoid interpretation and distortion when assessing a situation for myself.

However, we have already gone too far. Let’s return to listening itself.

Although we’re doing our best here to explain what listening is, it’s hard to explain how to listen without discussing what not to do. We recommend looking out for three types of distraction: interpretation, ideation and composition.

Interpretation

For example, a customer (internal or external) is explaining their issues with a report that I’ve written. They say, “… and I’m afraid that the cost analysis section isn’t clear enough …”. It’s a Difficult Conversation because I’ve worked hard on the report, I’m proud of it and I find criticism hard to take. On the customer’s side, they urgently certain information and they’ve been requesting it for some time. Everyone is on edge.

If I make a genuine attempt to understand my customer’s problem – to see why the report isn’t clear enough to them – then they will probably feel reassured and will cooperate with me, allowing us to fix the issues together.

However, if I tell myself, for example, “they’re stupid” (judgement) or, “you can’t expect a report like this to be clear first time – you’ve got to work through the figures” (rule/generalisation) or, “they think writing this sort of thing is easy!” (supposition/projection), then I start a negative train of thought and I cease to listen.

Ideation

More generally, because of the way that our brains are built, new ideas can be triggered in unpredictable ways by the stream of information that I’m listening to. Before I know it, I find myself daydreaming.

To continue with the example of a customer who’s says, “… and I’m afraid that the cost analysis section isn’t clear enough …”, perhaps they are screen-sharing a page of the report and, when they say “clear enough”, this triggers a flood of ideas about possible improvements to the report’s colour scheme. My brain rejoices in this opportunity to imagine possible improvements that I could make to the report’s appearance – and perhaps to all of the documents I produce, perhaps even to department policy. I stop listening in order to follow these distracting ideas through my excited neural pathways…

Composition

I recall, for example, the reason for my choice of axes on the graph that we are currently reviewing, thinking about how I can impress upon my customer the wisdom of this choice and why it’s so much better than traditional approaches. Perhaps I should start my reply with something like, “I really appreciate your comments. Not many people take the time to go into so much detail …”?

These thoughts about what I am going to say next are both unnecessary and damaging.

They are unnecessary if I have the presence and patience to pause after listening (as recommended in our article on the Troll-Taming Loop). It’s in this pause, once I have heard what the other person has to say, that I should compose my reply.

They can damage the relationship with the other person when they realise that I have not been listening. The speed with which I respond to what they’ve said gives me away. If I’d paused before giving a thoughtful reply, then it would have shown that I’d been listening. But when, in the microsecond that the other person stops talking, I respond with a self-serving comment or question, then it’s obvious that I haven’t heard a word of what they just said!

When testing the limits, I must listen with all my senses

Everyone interprets, ideates and composes when they should be listening. It’s automatic! The trick is to recognise these distractions and to put them aside as quickly as possible in order to return to listening.

Taking notes may help – scribbling a couple of words that capture a distracting idea allows me to concentrate on the other person again, for example. I can come back to the idea later.

I may also ask for assistance: “I’m sorry, I got distracted for a second – could you repeat that?”. This mini-interruption is a genuine sign that I am trying to listen!

When in a difficult conversation, I’m constantly testing the limits of my relationship with another person, going as far as I can without falling into conflict. They are in the same position. We have to work this out together.

It’s the very stuff of management, leadership, coaching, customer-facing work and many other challenging activities. Invigorating stuff. It’s like skiing fast downhill, avoiding the obstacles and pitfalls, on the edge but intent on not going beyond that edge and taking a spectacular fall.

The descent cannot go on forever, of course, and just as I want to return to a normal conversation, I am relieved when the slope finally reduces to something that I can handle easily. Sometimes, however, quite the opposite happens. I find myself going ever faster downwards, skidding over hard ice, perhaps careering towards the edge of a cliff. Difficult conversations can go this way too, in which case I must recognize the danger and know how to stop.

The skiing metaphor also says something about how we should approach difficult conversations: boldly, expecting to have an exhilarating experience. Those who come to most grief on the slopes are those who most fear a fall. It’s the same with difficult conversations -fear is my worst enemy and there’s no need for it, especially if I’ve worked on my skills.

In particular, I must learn to listen constantly with all my senses!

Stay safe and work hard

We started this article on a cross-country bike then went onto a motorway before ending up in a difficult meeting. And we’re finishing with downhill skiing! Whichever metaphor you prefer for Difficult Conversations, including troll taming, they all combine danger with excitement!

We’d therefore like to end this series of articles by inviting you to take care. Remember that the flow we have been describing includes the possibility to end the conversation, either temporarily or permanently, if things go badly. At the same time, our experience shows that Difficult Conversations go better and better with practice – deliberate practice – and we encourage you to leverage the ideas and tools we’ve discussed in order to help this process.

Good luck. Bon courage!

Andrew Betts and colleagues

Last modified: 31 July 2022

[1] One could argue that, practically speaking, this kind of request has to be made in the interests of completing the feedback process on time. We would agree with this if the feedback process were simply a bureaucratic procedure that nobody paid any attention to. On the other hand, if its real purpose is to reinforce the relationship with the team member and create an environment where they perform better, then the procedural deadline may have to be sacrificed this once.

[2] Even these constructive interruptions may be ill advised when the other person is angry or irritated. When faced with someone in this state, attentive listening is usually the best way to restore calm. Almost anything I say will trigger more anger or irritation.

[3] Feelings are combinations of emotions. The number of possible emotions is relatively small – between 4 and 7, depending on interpretations. Joy, anger, fear and sadness are widely accepted. Surprise, disgust and guilt appear in some lists. Since feelings are combinations of emotions, they are many – in the range of 50 to 100. See https://www.cnvc.org/training/resource/feelings-inventory, for example.

---

Other articles in this series

English articles : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , summary and notebook

Traductions en français : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , sommaire et cahier

Your feedback and suggestions

The Difficult Conversations eBook and articles are the result of many hours of collaborative work and they build upon a huge base of established wisdom.

I am grateful to everyone involved so far – trainees, fellow trainers and coaches, other authors … and I would also appreciate your comments and suggestions!

There is an online form or, if you prefer, an email to contact@icondasolutions.com would be fine.

As you may have noticed, ...

... the topics in this series on Difficult Conversations are organised hierarchically:

- Article 1: At the top level, a Difficult Conversation can be imagined as a bridge with a troll blocking the way, where the troll represents the Difficult Exchange which has to be sorted out before a normal conversation can resume. Our challenge is to tame the troll.

- Article 2: At the next level, we break our troll-taming method down into a four step loop: pause, say, invite and listen/decide. We go around this loop until we've Reconciled the Difficult Exchange and have returned to a normal conversation (dialog).

- Articles 3-7: Finally, each of the four steps has its own internal details and the refinement of these details takes us deeper still, as with any substantial subject.

We invite you to use the tools and models described in these articles to guide your practice and we hope that you find this hierarchical description helpful.

Comments, suggestions and enquires: contact@icondasolutions.com