Suraj and I broadcast a podcast on Difficult Conversations a few days ago and we asked participants for ideas on best practices. “Focus on the problem” was suggested and the person who’d suggested this explained: when confronting someone , talk about the issue and avoid any criticism, however indirect or discreet, of the person.

In our view, this nicely captures one of the most important principles of dealing with difficult conversations. There’s only one slight problem: how do we avoid being critical?

Start with brief, factual observations

A fundamental principle of reconciling Difficult Exchanges is that we talk to the troll without provoking defensiveness or aggression. The troll, you may recall from previous articles, represents the confusion of emotions disrupting our communication. When I approach him, my best bet is to start with brief, factual observations.

Isn’t there a funny smell in here?

Let’s say I’m talking to a close colleague – in the sense that we occupy the same, small office – about his cycle into work. Particularly about the uphill aspect, it’s perspirational consequences and the resulting odor. In other words, I’m trying to tell him that he smells.

Suppose I say, “Alfred, you’re probably not aware of this, and I’m sure you can’t help it after all the cycling uphill and stuff, but there’s a funny, sweaty smell hanging around here. As you know, with clients visiting and all, we’ve got to be careful that …”. This may seem reasonable – after all, I have been thinking about how to say this for days. Unfortunately, this preparation is the first problem.

Don’t prepare for verbosity

Self-restraint is crucial when tackling Difficult Exchanges. I need to understand how the other party reacts to my attempts at communication as quickly as possible and a simple way to do this is to invite them to speak before saying too much.

Don’t fuel an argument

The second problem is that, in this example, I’ve provided several triggers for an argument :

- “you’re probably not aware of this” is a supposition

- “funny, sweaty smell” contains a judgment

- “we’ve got to be careful that …” is a rule

If Alfred is in a bad mood or feeling sensitive, he might respond with, for example:

- “Are you calling me stupid? Of course I’m aware of it …”

- “What do you mean ‘funny’?? It’s just normal, clean sweat! If you got off your butt occasionally you might know more about it …”

- “Don’t you tell me about how to look after visitors. I’ve been doing this job for 20 years and …”

It’s not that there’s anything intrinsically wrong with suppositions, judgements and rules, it’s that I should not present them as though they were facts. If I were to say, “I suppose that you’re not aware of this …”, “I’m disturbed by a smell in this office” and “I believe that we should be careful …”, then we would be in the clear.

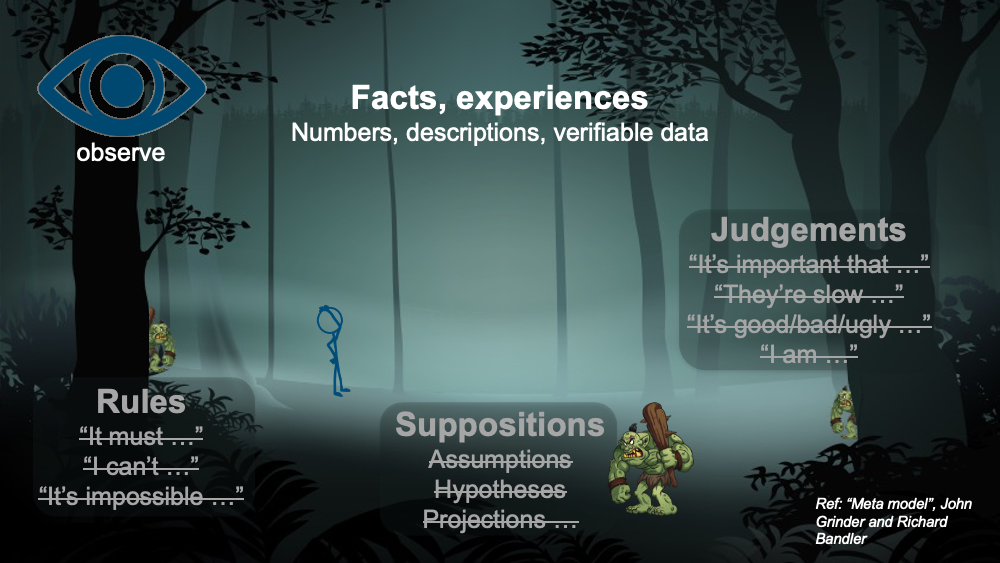

However, disguised judgements, implied rules and hidden suppositions are dangerous, particularly in circumstances where the other party might feel vulnerable and is likely to become defensive or aggressive. Unless I avoid these second-order interpretations and stick to first-order, factual observations, I greatly increase the risk of a heated reaction. An interpretation is, by definition, subjective, unprovable and incendiary. This is because:

- Disguised judgments imply and impose my values

- Implied rules (also known as generalizations) impose my beliefs

- Hidden suppositions imply things which aren’t necessarily true

In contrast, a factual observation can be checked and corrected if necessary. If someone says that our last meeting was on 23rd and it was really on the 24th, then this error can be quickly fixed. If, on the other hand, they say that we haven’t had a meeting for ages, then they are stating an arguable point as though it were a fact.

Other ideas on how to end up in a fight

![]()

Let’s look at judgements, rules and suppositions in more detail, starting with a variety of new examples:

- Example 1: “It’s important to make the release this week”, contains two things: (1 ) information on when a release is expected or needed and (2 ) a judgment, “it’s important”. We find hidden judgments in all kinds of text and speech – take a look at any newspaper!

- Example 2: “The release should be made this week”. In addition to the same information as in the previous example, we have what’s called a rule: “it should be done this week”. Who says so!?

- Example 3: “If the release isn’t made this week, the customer’s going to be upset”. Again, it’s the same information, but hidden in the phrase is a projection about the customer’s state of mind. However, I can’t know this unless I’ve checked with the customer. If I have, then it would be less provocative to say so explicitly.

Depending on their current mental state – on how tired, vulnerable, irritable, etc they are feeling – the other party might object to any one of the above:

- In the first case, they may respond with, “But XYZ is much more important”. The conversation has become an argument opposing one set of values with another.

- For the second example: “Who says it should be done this week? It’s a public holiday on Thursday and I deserve a break. The management should be more careful with its planning!”. We now have one set of beliefs up against another.

- And last but not least: “I don’t think so. Fred is pretty cool if he gets the release by next Wednesday. He won’t be at all bothered”. This is a contradictory view on something that can’t be properly resolved here and now.

In all three cases, with feelings running high, conflict is likely.

Notice that the three examples given sound innocuous at first. That’s because we say these sort of things all the time. These ways of expressing ourselves are short, convenient and a part of our cultural heritage. The alternative is more verbose and less intuitive but, in the context of a Difficult Exchange, far less likely to provoke conflict.

How to avoid a conflict

The image shown above reminds us of the three main pitfalls to avoid when attempting to “stay factual” and reminds us of what high-quality observations should contain: facts and experiences, typically in the forms of numbers, descriptions and verifiable data. Using this guideline, the preceding examples could be rewritten as follows:

- “The regression had 3,273 failing tests last night and I don’t think we will be able to make a release this week. However, that’s what I promised the customer at our meeting last Wednesday”.

- “We agreed with our customer that we would release the software this week I think that Fred would be upset if we didn’t do this”.

If we wish to embellish these statements, then we need to express feelings and needs also – the subject of a future article. However, to avoid frustration, here are a couple of ways in which this could be done accurately:

- “It’s important to me that we meet this deadline”.

- “I would be disappointed if we didn’t manage this”.

- “I fear that we won’t manage this and that our credibility with Fred will suffer as a result”.

Now, back to my smelly cubicle cohabitant …

Perhaps I could start with, “ Alfred, you’ve been cycling into work now for about 6 weeks every day unless it rains, right? ”.

Then it’s over to Alfred – I’m not delivering a prepared speech but simply starting a discussion. Alfred can either confirm or correct my data (perhaps it’s seven weeks?) or he could even guess where I’m going with this. He may have started to wonder about his sweat glands already, and so it’s not impossible that his response would be, “you’re going to tell me that I smell, right? ”. At this point, the difficult exchange is over and we’re back to a normal conversation. Job done.

However, if he simply confirms my observation, then I need to go further. “Well, I notice on the days that you cycle, that you’ve been sweating. Have you noticed this yourself?”

Again, I stay factual and concise. It’s crucial not to go too far without giving the other person a chance to react. Their reaction – if I listen and watch – will guide what I say next. Once again, the hard work could even be over at this point, if the message becomes clear to Alfred.

However, if it doesn’t and Alfred simply replies, “no”, I must continue. “OK, I can understand how you could miss this. On the other hand, three of our colleagues commented that our box smelt sweaty last week . Given that I’ve noticed this and others have too, what do you think ?”.

At this point, Alfred may acknowledge that there is an issue and we discuss what can be done (we’d be back to a normal discussion ). If not, and assuming that I don’t have any fancy measuring equipment to hand with which to prove my case, then I have a decision to make. Do I consider that Alfred has really not understood, or do I now believe that refuses to discuss the issue? In the first case, I will continue to carefully explain the problem that I perceive, perhaps moving the conversation on to the difficulties that this situation is causing me (we’ll discuss how this might be done in a future article) else I might decide to stop here.

It’s important to remember that I have the option to abort the conversation. It is not always possible to reconcile a Difficult Exchange and it’s important to recognize when our best efforts have failed. If we don’t, then the likely consequences are:

- We become progressively more frustrated, both with ourselves and the other person, and this makes the situation worse, increasing the chances of damaging the relationship

- We miss the opportunity to take alternative, timely action.

“Alternative, timely action” is a nice way of saying, “fight or flight” [2]. In a professional context, “fight” often means escalating an issue to management and flight means withdrawal – avoiding or working around a problem, rather than solving it. In this example, I could move offices, for example.

Summing up

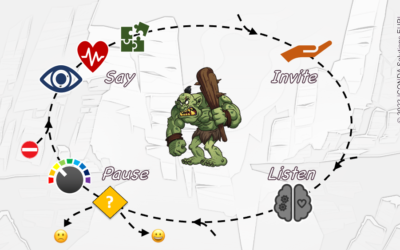

The example above uses the Troll-Taming Loop “looping flow” for the reconciliation of Difficult Exchanges.

It can be seen that, although the idea of approaching difficult exchanges from a factual standpoint is a simple concept, it’s tricky to do. Concealed judgements, rules and suppositions slip easily into our speech. Furthermore, it’s extremely important not to make a speech! I must keep it brief and give the other person a chance to speak, allowing their responses guide my next comments.

Of course, even though factual observations are unlikely to provoke the troll they may not calm him completely. In the next couple of articles, we’ll therefore look at the (equally tricky) business of expressing feelings and needs.

Andrew Betts an colleagues (first draft)

Last modified: 31 July 2022

[1] We see this countless times when people prepare for interviews, either as the person leading the interview or as a candidate. A manager informing a team member about poor performance may think of many justifications for the ratings they have awarded and the recovery action they envisage then, challenged by the lack of reaction to their initial announcement, they just keep talking. A job candidate, knowing that they will be asked to talk about their background, prepares a comprehensive summary and then, when given the chance, delivers the whole thing in one go.

[2] This “Listen & Decide” step is described in our article on the Troll-Taming Loop.

---

Other articles in this series

English articles : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , summary and notebook

Traductions en français : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , sommaire et cahier

Your feedback and suggestions

The Difficult Conversations eBook and articles are the result of many hours of collaborative work and they build upon a huge base of established wisdom.

I am grateful to everyone involved so far – trainees, fellow trainers and coaches, other authors … and I would also appreciate your comments and suggestions!

There is an online form or, if you prefer, an email to contact@icondasolutions.com would be fine.

As you may have noticed, ...

... the topics in this series on Difficult Conversations are organised hierarchically:

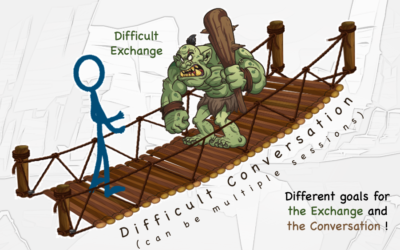

- Article 1: At the top level, a Difficult Conversation can be imagined as a bridge with a troll blocking the way, where the troll represents the Difficult Exchange which has to be sorted out before a normal conversation can resume. Our challenge is to tame the troll.

- Article 2: At the next level, we break our troll-taming method down into a four step loop: pause, say, invite and listen/decide. We go around this loop until we've Reconciled the Difficult Exchange and have returned to a normal conversation (dialog).

- Articles 3-7: Finally, each of the four steps has its own internal details and the refinement of these details takes us deeper still, as with any substantial subject.

We invite you to use the tools and models described in these articles to guide your practice and we hope that you find this hierarchical description helpful.

Comments, suggestions and enquires: contact@icondasolutions.com